By Kenneth Ukoh: Updated February 9, 2026

“People travel to wonder at the height of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motion of the stars; and they pass by themselves without wondering.”– Saint Augustine

Goal striving is an essential part of human beings.“Behaviour is basically the goal-directed attempt of the organism to satisfy its needs as experienced, in the field as perceived” (Rogers, 1951). However, what should be the basis for selecting and pursuing goals? Should we choose and pursue our goals because they are “SMART” or because they are self-concordant? This question is answered in this article on self-concordant goals.

Research has shown that ineffective goal pursuit may lead to abandoning goals. In some cases, a goal may be achieved without satisfaction with the outcome, or people may not be happier because of pursuing the wrong goals. We discussed the importance of selecting goals that are congruent with an individual’s sense of self in Part 5, on conation. In practice, the basis of choosing and setting a goal is that it meets the SMART criteria. However, research has shown that self-concordant goals are more likely to be attained as such goals, by their nature, energise people as they enhance well-being when they are achieved.

Kennon Sheldon and colleagues have proposed goal self-concordance to help people optimise their goal pursuit. It is derived from Self Determination Theory (SDT), which provides a broad framework for understanding motivation. SDT consists of six mini-theories, namely:

- The Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) deals with intrinsic motivation.

- The Organismic Integration Theory (OIT) is concerned with extrinsic motivation.

- The Causality Orientations Theory (COT) addresses how people regulate behaviour depending on the environment.

- Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT) deals with conditions that promote optimal functioning and psychological well-being through the satisfaction of basic needs.

- Goal Contents Theory (GCT) shows that whether a goal is chosen for extrinsic reasons or intrinsic reasons determines its impact on well-being.

- Relationship Motivation Theory (RMT) explains how the development and maintenance of close personal relationships promote adjustment and well-being.

We are going to examine the main principles of SDT that directly affect goal pursuit as appropriate in this article, but we will talk about it again in the section on Self-Regulation.

Self-Determination Theory and Self-Concordant Goals

According to SDT, human beings possess innate growth tendencies, and when they are given a supportive social environment, they naturally look for experiences that promote growth and development. The prerequisite for human development and growth is satisfaction with basic needs. These basic needs are autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Goals are the vehicle that people use to meet these needs, but according to SDT research, the content of goals determines whether the goal is beneficial in promoting growth and well-being. For instance, Intrinsic goals such as personal growth, fulfilment of values, meaningful relationships, etc., directly fulfil basic psychological needs and promote well-being. In contrast, extrinsic goals such as fame, wealth, beauty, etc. are associated with comparisons with others and seeking approval, and where such goals are given priority over intrinsic goals, it is incongruent with the satisfaction of basic needs and does not promote flourishing. SDT research on goals shows that wealth, beauty, and fame don’t equate with well-being.

Sheldon and his team (Sheldon and Elliot,1999) conducted a series of studies which show that when people pursue self-concordant goals, they are more likely to be energised to put more effort into attaining them, and when they attain them, they reap more benefits (Bono and Judge, 2003). The reason is that autonomous goals represent a person’s core values and beliefs, compared with goals based on controlled motivation, which are adopted because of environmental pressures and obligations. Whether a goal is autonomous or controlled does not necessarily depend on the content of the goal, but on the way the individual perceives the importance of the goal to him or her.

Following the impressive results of their studies, Sheldon and Elliot (1999) proposed the self-concordance model, which shows that self-concordant goals are congruent with one’s values and interests and lead to goal attainment and improvement of well-being.

The Self-Concordance Model (SCM)

Figure 1 – The Self-Concordance Model

Wan, P. et al. (2021). Goal Self-Concordance Model: What Have We Learned and Where are We Going, International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. Tech Science Press. Available at: https://www.techscience.com/IJMHP/v23n2/42430/html (Accessed: December 31, 2022).

Source: https://www.techscience.com/IJMHP/v23n2/42430/html

The Self-Concordance Model (SCM), Figure 1, is an approach to healthy goal striving. It is defined as “the rated extent to which people pursue their set of personal goals with feelings of intrinsic interest and identity congruence, rather than with feelings of introjected guilt and external compulsion” (Sheldon & Houser-Marko, 2001). The “self” in the model refers to “goals that are highly consistent with individual interests and intrinsic value beliefs” (Wan, P. et al. 2021). In other words, self-concordant goals are goals that are aligned with who we are, our authentic selves, and our values and beliefs. By contrast, goals that do not reflect individual interests or values have fewer chances of being achieved, and they contribute less to happiness even when they are attained. This shows that no matter how “SMART” goals are, they are less likely to be achieved and even when they are achieved, they contribute less to well-being if they are not self-concordant.

Self-concordant goals are also known as authentic, autonomous, intrinsic, or self-congruent goals. In their study, Sheldon & Houser-Marko (2001) found that people who set self-concordant goals enjoy the experience of authenticity and an upward emotional spiral that contributes to greater well-being, happiness and life satisfaction.

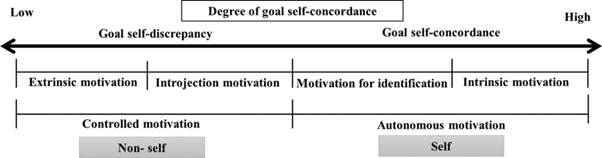

Such goals may include pursuing a goal because it is inherently fun (intrinsic), it is aligned with an individual’s broader life goals (integrated), and/or it is personally meaningful and important (identified). By contrast, goals that are pursued to comply with internal or external demands tend to engender the feeling of being controlled. Such goals tend to be less representative of an individual’s own interests and values and instead are often pursued to stop anxiety and guilt (introjected) or to get approval from others (external). According to self-determination theory, these types of motivation fall along a continuum (Ryan & Connell, 1989), representing the extent to which an individual functions in a relatively autonomous versus controlled manner. Similarly, Sheldon and Elliot treat self-concordant goals as a continuum, forming a composite of the two controlled (external and introjected) and two autonomously motivated (identified and intrinsic) reasons for acting as shown in Figure 1 above.

The Self-Concordance Model (SCM), The Perceived Locus of Causality (PLOC) and Internalisation Theory.

One of the mini theories of Self-Determination Theory is Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), which identifies intrinsic and extrinsic motivations as the two types of motivations that drive behaviour. When a person is doing something that lacks both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, this is known as “amotivation“. For example, the person does not find engaging in such an activity worthwhile. It is also known as “avolition.” “Amotivation, also known as avolition, is a psychological condition defined as “a reduction in the motivation to initiate or persist in goal-directed behaviour”. Motivation enables an individual to sustain rewarding value of an action into an uncertain future. Thus, amotivation affects the subjective and behavioural aspects of goal-directed activity” (Lee et al., 2015).

However, though intrinsic motivation contrasts with extrinsic motivation, in SDT, extrinsic motivation is seen to vary greatly in the degree to which it is autonomous. For this reason, the different types of motivation are expressed in a continuum that represents the level of the individual’s self-determination. According to the Organismic Integration Theory (OIT), extrinsic motivation is made up of four behavioural regulations increasing in their degree of self-determination or autonomy as follows:

- The less self-determined form of extrinsic motivation is external regulation, which reflects the influence of external pressures or rewards on the behaviour.

- Next, introjected regulation reflects self-imposed pressures like guilt, shame, or ego protection. These two behavioural regulations express a form of external control in individual behaviour.

- Identified regulation refers to the recognition and acceptance of the importance of a behaviour.

- Integrated regulation is a manifestation of the pursuit of an activity because it is in line with one’s core values and sense of self. It represents a gradual transition to more autonomous forms of motivation.

Ryan & Connell (1989) developed the Perceived Locus of Causality (PLOC) scale for the measurement of external regulation, introjection, identification, and intrinsic motivation. The Perceived Locus of Causality (PLOC) is based on the Theory of Internalisation. (Ryan & Connell, 1989). “Internalisation is assimilating other people’s ideas into your own.” (N., Sam M.S., “INTERNALIZATION,” in PsychologyDictionary.org, May 11, 2013). Using a goal as an example, PLOC measures the degree to which people regard a goal as their own (i.e., the degree of internalisation of the goal). According to SDT, internalisation and integration are developmental processes that are catalysed by socio-cultural conditions that support the satisfaction of the three basic needs. This proposition has received considerable empirical support (Deci & Ryan, 2002). So, for people who work with clients and managers, it is essential that the goals of the people they work with are owned by them.

Measurement of Goal-Self Concordance

Figure 2: Degree of Goal Self-Concordance

Source: https://www.techscience.com/IJMHP/v23n2/42430/html

Wan, P. et al. (2021). Goal Self-Concordance Model: What Have We Learned and Where are We Going, International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. Tech Science Press. Available at: https://www.techscience.com/IJMHP/v23n2/42430/html (Accessed: December 31, 2022).

As Figure 2 above shows, the Perceived Locus of Causality (PLOC) is a representation of the continuum of the different forms of motivation, ranging from amotivation at one end to intrinsic motivation at the other. The continuum represents an index of relative autonomy perceived by the individual. When people have a more internal PLOC for behaviour, they will exert greater effort and experience greater satisfaction in performing the behaviour than when they have a more external PLOC. It is used as an index for measuring self-concordant goals.

One of the methods of measuring a self-concordant goal is described below (Wan, P. et al., 2021):

- People were asked to write down 5–15 goals that they are pursuing or setting.

- Then they ranked the goals according to the degree of internalisation of self-determination theory: external compulsion, identity adjustment, and internal adjustment. Controlled reasons included “because somebody else wants you to, or because you’ll get something from someone if you do” (external) and “because you would feel ashamed if you did not—you feel that you should try to accomplish this goal” (introjected). Autonomous reasons included “because you believe it is an important goal to have” (identified), “because of the fun and enjoyment which the goal will provide you—the primary reason is simply your interest in the experience itself” (intrinsic).

- Items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all for this reason) to 7 or 9 (completely for this reason).

- A measure of goal self-concordance was calculated by subtracting the average of the controlled items from the average of the autonomous items for each goal.

An overall score of goal self-concordance was calculated by taking the average of the self-concordant scores across all goals. A positive difference indicates a concordance between goal and self, and a higher value is positive relative to a higher level of goal self-concordance. While negative difference refers to goal self-non-concordance, a higher value also indicates a higher level of goal self-non-concordance.

The importance of Distinguishing Between Goals and Wishes or Desires

The research on goal pursuit is impressive, and it is aimed at making goal pursuit successful by enhancing attainment and improving, changing and transforming lives. In practice today, every aspect of goals is conflated under the SMART acronym. In contrast, research shows that goal pursuit is divided into different phases, which require different mindsets, as we shall see when we discuss the Rubicon Model below. For this reason, research differentiates between a wish or desire and a goal. It is in the deliberation phase that a decision is made to turn a wish or desire into a goal. It can be recalled that a goal is defined in Part 2 as a “cognitive representation of a desired end state that a person is committed to attain” (Milyavskaya and Werner, 2018). On the other hand, a wish is defined by the APA Dictionary of Psychology as:

- “In classical psychoanalytic theory, the psychological manifestation of a biological instinct that operates on a conscious or unconscious level.”

- “In general language, any desire or longing.”

So, the difference between a goal and a wish or desire is the commitment which occurs by means of goal-directed behaviour. The process of goal-directed behaviour can be meaningfully divided into four stages: the establishment stage, the planning stage, the goal-striving stage, and the revision stage (Bongers & Dijksterhuis, 2009). This corresponds in stages to the Rubicon Model of Action Phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2007), which we discuss below.

In their motivational Theory of Action Phases, Heckhausen and Gollwitzer (1987) propose that our motives produce more wishes and desires than can be realised because of limited resources and priorities. Consequently, we are compelled to choose which one to pursue as a goal. This choice involves a process of deliberation based on the feasibility and desirability of the one chosen. In other words, only feasible and attractive wishes or desires are turned into goals, which then lead to the initiation of goal-directed behaviours.

The Rubicon Model of Action Phases

Figure 3: The Rubicon model of action phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2007)

Before continuing the discussion on the Rubicon Model and goal selection. We would like to point out that not all goals are chosen intentionally or consciously, as research has shown that goals can be pursued unconsciously. So, this article is concerned with intentional goal pursuit. We will do a separate article on unconscious goal pursuits later.

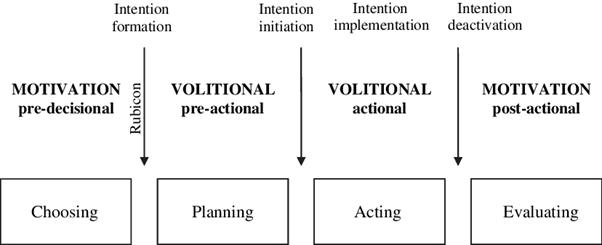

The Mindset Theory of Action Phases (Gollwitzer, 2012) and the Rubicon Model of Action Phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2007) have been developed to facilitate goal attainment by showing that goal pursuit involves different phases and so, different emphasis and attitudes. Consequently, to improve our chances of success, we must understand the different stages and follow the appropriate processes.

According to Achtziger & Gollwitzer (2007), the Rubicon Model has been developed to answer the following questions:

- “How do people select their goals? “

- “How do they plan the execution of those goals?”

- “How do they enact these plans?”

- “How do they evaluate their efforts to accomplish specific goals?”

The Mindset Theory of Action Phases (MAP) distinguishes two broad phases of goal pursuit and four distinct and successive phases of action (Gollwitzer & Keller, 2020). These different phases of action are depicted on The Rubicon Model of Action Phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2007).

The two broad phases are the motivational (i.e., the pre-decisional and the post-actional phases and the volitional (the pre-actional and the actional phases. The pre-decisional and the post-actional phases are concerned with evaluating the reason for pursuing a goal, while the pre-actional and the actional phases focus on how the goal will be pursued. These two broad phases are described in the four distinct phases of the Rubicon Model, which we are going to discuss in the next section.

The Four Distinct Phases of Goal Pursuit

The Rubicon Model of Action Phases identifies four distinct phases of goal pursuit (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2007):

- The pre-decisional phase involves the deliberation of the pros and cons of the desirability and feasibility of the wish or desire because, at this point, it is not yet a goal.

- The post-decisional phase comes after the decision has been made and the desire is now turned into a goal. This involves planning the implementation of the goal by deciding when, where and how to act toward the goal.

- The action phase occurs when goal-directed behaviour and progress are made toward the goal and brings the goal to a successful end.

- This is the post-actional phase, where the outcome is evaluated to see whether the outcome has been met or if there is more to be done.

These four phases are separated by three distinct transition points:

- The point where a decision is made to strive for the desire, and in this way, turn the desire into a goal. This is the end of the pre-decisional phase. The transition point here is known as “the transition of the Rubicon.” The phrase, crossing the Rubicon, is used to mean that a decision has been made and a point has been reached where the decision or course of action cannot be changed. The phrase is borrowed from the event when General Julius Caesar entered Roman territory by crossing the Rubicon, a stream in what is now Northern Italy and started a civil war that marked the end of the Roman Republic.

- The second transition is the initiation of appropriate actions to attain the goal at the end of the pre-actional phase.

- The third transition is at the end of the actional phase, when the outcome of the goal is evaluated to assess whether the goal has been achieved or not.

Goal Setting and Goal Striving Have Different Processes

Research has overwhelmingly emphasised the importance of attaining goals for human flourishing since human beings are goal-oriented. Despite the numerous studies that have been carried out to show that goal pursuit and attainment involve various processes, stages, attitudes and behaviour. However, the most popular method of goal pursuit in practice, the “SMART” method, assumes that everybody is the same and so, anyone who wants to pursue a goal evaluates a goal based on the SMART requirements, and once those requirements are met, success can be achieved. But people are different. Emotions play a big part in our lives, and goal pursuit is not an exception.

When people pursue goals, they are trying to learn new behaviours. Considering individual differences in the way people adapt to new behaviours or even resent them, it is not surprising that most people have wishes or desires, but they don’t know how to turn them into achievable goals because the SMART method does not help them to learn how to do so and cannot help them to deal with motivation and self-regulation which are critical to goal attainment. According to Nowack, (2017), the availability and type of social support (Chiaburu, Van Dam, & Hutchins, 2010; Martin, 2010; Orehek & Forest, 2016) as well as the regulation of emotions are equal to, or even more important than, cognitions in predicting both intention and initiation of new habits (Lawton, Conner, & McEachan, 2009).

Both the Rubicon Model and the Goal-Self Concordance Model have shown that goal selection matters because there is no value in wasting time to attain a goal that is of no value. So, it is important to properly analyse a potential goal before it is selected. The research on goal self-concordance is mainly with reference to the stage when a goal has already been chosen. The same principle can be used to evaluate potential goals during the deliberation stage, like the Rubicon Model.

Goal striving is an essential nature of human beings. “Behaviour is basically the goal-directed attempt of the organism to satisfy its needs as experienced, in the field as perceived” (Rogers, 1951). However, what should be the basis for selecting and pursuing goals? Should we select and pursue our goals because they are “SMART” or because they are self-concordant? This question is answered in this article on self-concordant. So, find out here how to choose and pursue goals that will promote your personal growth and well-being.

References

Achtziger, Anja & Gollwitzer, Peter. (2007). Rubicon Model of Action Phases. First publ. in: Encyclopedia of social psychology 2 (2007), pp. 769-770.

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). Wish. [online] Available at: https://dictionary.apa.org/wish [Accessed 3 Feb. 2023].

Bongers, K.C.A. & Dijksterhuis, Ap. (2009). Unconscious Goals and Motivation. 10.1016/B978-012373873-8.00082-7.

Bono, Joyce & Judge, Timothy. (2003). Self-Concordance at Work: Toward Understanding the Motivational Effects of Transformational Leaders. Academy of Management Journal. 46. 554-571. 10.2307/30040649.

Gollwitzer, Peter. (2012). Mindset theory of action phases. 10.4135/9781446249215.n26.

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992338

Lee, J. S., Jung, S., Park, I. H., & Kim, J. J. (2015). Neural Basis of Anhedonia and Amotivation in Patients with Schizophrenia: The Role of Reward System. Current neuropharmacology, 13(6), 750–759. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159×13666150612230333

Milyavskaya, M., Nadolny, D. and Koestner, R., 2014. Where Do Self-Concordant Goals Come From? The Role of Domain-Specific Psychological Need Satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(6), pp.700-711.

N., Sam M.S., “INTERNALIZATION,” in PsychologyDictionary.org, May 11, 2013, https://psychologydictionary.org/internalization/ (accessed January 12, 2023).

Nowack, K. (2017). Facilitating successful behaviour change: Beyond goal setting to goal flourishing. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(3), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000088

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centred Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory. London: Robinson.

Rose, N. (2014) To Thine Own Self Be True”: Self-Concordance and Healthy Goal-Striving, Mappalicious – The German Side of Positive Psychology. Available at: https://mappalicious.com/2014/06/27/to-thine-own-self-be-true-self-concordance-and-healthy-goal-striving/ (Accessed: December 31, 2022).

Ryan, R.M., & Connell, J.P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of personality and social psychology, 57 5, 749-61.

Sheldon, K., Elliot, A., Ryan, R., Chirkov, V., Kim, Y., Wu, C., Demir, M. and Sun, Z., 2004. Self-Concordance and Subjective Well-Being in Four Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), pp.209-223.

Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482

Sheldon, K., Elliot, A., Ryan, R., Chirkov, V., Kim, Y., Wu, C., Demir, M. and Sun, Z., 2004. Self-Concordance and Subjective Well-Being in Four Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), pp.209-223.

Sheldon, K., 2014. Becoming Oneself: The Central Role of Self-Concordant Goal Selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), pp.349-365.

Sheldon, K., 2019. Which Way Should I Go? | Society for Personality and Social Psychology. [online] Spsp.org. Available at: <https://spsp.org/news-center/character-context-blog/which-way-should-i-go> [Accessed 14 August 2022].

Sheldon, K., 2019. Which Way Should I Go? | Society for Personality and Social Psychology. [online] Spsp.org. Available at: <https://spsp.org/news-center/character-context-blog/which-way-should-i-go> [Accessed 14 August 2022].

Sheldon, K. and Elliot, A., 1999. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), pp.482-497.

Sheldon, Kennon & Houser-Marko, Linda. (2001). Self-concordance, goal attainment, and the pursuit of happiness: Can there be an upward spiral? Journal of personality and social psychology. 80. 152-65. 10.1037//0022-3514.80.1.152.

Wan, P. et al. (2021) Goal Self-Concordance Model: What Have We Learned and Where are We Going, International Journal of Mental Health Promotion. Tech Science Press. Available at: https://www.techscience.com/IJMHP/v23n2/42430/html (Accessed: December 31, 2022).