“Spending time with negative people can be the fastest way to ruin a good mood. Their pessimistic outlooks and gloomy attitude can decrease our motivation and change the way we feel. But allowing a negative person to dictate your emotions gives them too much power in your life. Make a conscious effort to choose your attitude.” – Amy Morin

By Kenneth Ukoh, Updated February 13, 2026

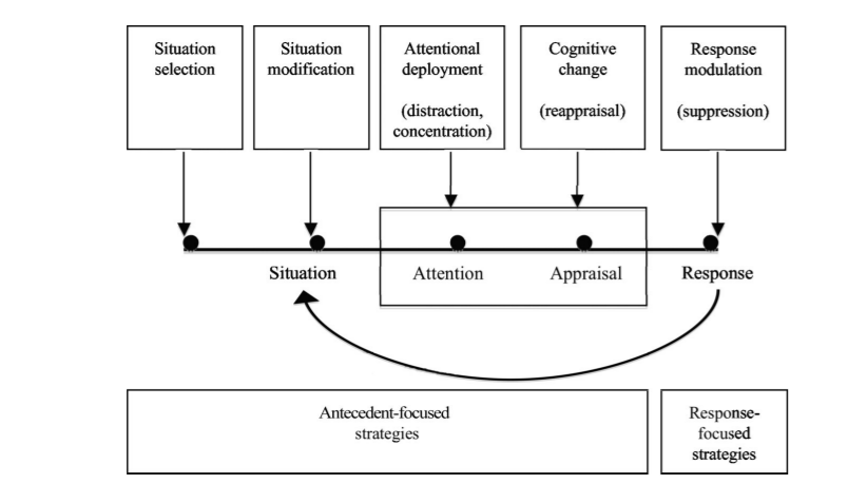

The Process Model of Emotion Regulation

Source: Psychology of Human Emotion: An Open Access Textbook

Different emotion regulation strategies have been proposed because there are different ways people can regulate their emotions. However, the most widely cited depiction among researchers is the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 2015).

This model views emotion regulation as a process and identifies five interconnected strategies that can be used to change the course of the emotion and how it is experienced. These are situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. It suggests that emotion regulation strategies that intervene early in the process are likely to be more effective than strategies that intervene later, after emotional response tendencies are activated (Sheppes and Gross, 2012).

The model predicts that specific strategies chosen will bring different outcomes, for example, in how the person feels, thinks, and acts, both immediately and over the longer term. This prediction arises from two related ideas:

- Emotions develop over time and intervene at different points in the emotion-generative process, manifesting in different patterns of emotional experience, expression, and physiology.

- Different emotion regulation strategies make different cognitive demands. So, these differences might have consequences because emotion regulation may be viewed as altering the emotion trajectory that would have occurred in the absence of that strategy. Antecedent-Focused and Response-Focused.

Antecedent-Focused and Response-Focused.

Gross (1998) categorises these strategies into antecedent-focused and response-focused.

- Antecedent-focused regulation occurs before the emotion is fully experienced or during the experience, whereas response-focused regulation occurs after the emotion has completely developed. Antecedent-focused strategies are employed early in the process. It refers to cognitive changes employed in response to a situation and happens before emotional responses are manifest. They occur when we alter the eliciting event (situation selection, situation modification) or when we alter our cognitions (attention deployment, cognitive change).

- With response-focused, people have already “responded” to the eliciting event and have experienced all the emotional changes. In response-focused people can regulate emotions by trying to change any of the components. They might change their facial expressions and vocal tone, suppress their thoughts, increase or decrease their physiological arousal, and even change their subjective feelings.

Situation Selection.

Situation selection is the strategy that occurs earliest in the emotion experience. It means choosing situations or environments most likely to generate pleasant emotions and knowing which situations lead to undesirable emotions and choosing to avoid them.

Recently, Gross (2015b) has expanded his original model which he refers to as the Extended Process Model of Emotion Regulation which incorporates the concept of interacting valuation systems, now referring to the model as the extended process model of emotion regulation. In the expanded model, there are three valuation systems (with each unfolding through a process of perception, valuation, and action, which are involved in emotion regulation. They are distinguished by where they occur in the emotion regulation process as follows:

- The first stage, identification, involves the detection of an emotion (perception), its evaluation as an experience that requires regulation (valuation), and a decision about whether regulation will begin (action).

- The second stage, selection, involves the identification of available emotion regulation strategies (perception), evaluation of whether specific strategies will be more or less successful depending on internal and external contextual factors (valuation), and making the choice to use a particular strategy (action).

- The third and final stage, implementation, involves translating a general emotion regulation strategy into specific behaviours that would be most suitable for that specific situation (perception), evaluating the likely effectiveness or ineffectiveness of specific emotion regulation strategies (valuation), and actually choosing and implementing a specific emotion regulation strategy (action).

Situation Modification

This strategy can be used when we are already in a situation that is likely to make us feel an undesirable emotion. We can use it to change or improve the emotional impact of the situation. However, modifying a selected situation may mean that a new situation has been created, as altering the situation could cause us to enter a new situation Gross, (2008). So, situation selection and modification may not be totally different. For example, if a conversation leads to a heated argument, you may change the topic to stop the argument from escalating further.

For example, when a conversation gets heated, you can stop the debate from degenerating and agree to disagree.

Attentional Deployment

We have already discussed in Part 9 the importance of using attention for self-regulation.

Attention deployment is sometimes referred to as distraction. It is an emotion regulation strategy which involves redirecting the focus of attention to change their emotional experience (Gross, 2013). During goal pursuit, we may be faced with high-pressure situation which affects our ability to sustain sufficient levels of performance.

Attentional deployment, or diverting your attention, literally means changing your mind. It involves directing or focusing your attention on different aspects of a situation or on something completely unrelated. For example, say you are afraid of needles, but to get your vaccine, you choose not to think about it, and you concentrate your attention on a happy memory.

Cognitive Reappraisal

Cognitive reappraisal means changing the perception of a situation. It means thinking about things differently to change the way you feel. This may be by focusing on the bright side of things instead of the negatives. For example, you have just lost your job, and you choose to see this as an opportunity to do something new and explore new passions.

Cognitive reappraisal is the main form of cognitive change. It involves using “cognitive skills (e.g., perspective-taking, challenging interpretations, reframing the meaning of situations) to modify the meaning of a stimulus or situation that gives rise to emotional reactivity.” (Goldin, Jazaieri and Gross, 2014).

Two different types of reappraisal have been identified: detached and positive reappraisal (Liang et al., 2017). In detached reappraisal, the idea is to remove yourself from the emotional situation and reframe the stimuli to reduce their potency. In positive reappraisal, we engage with the experience and attempt to reinterpret it positively.

In detached reappraisal, individuals deliberately consider the situation from an unemotional and detached perspective; whereas in positive reappraisal, individuals focus on negative aspects of the situation and try to reinterpret the situation in terms of potential positive outcomes.

It targets the appraisal stage, and according to Troy et al. (2018), it is thought to be an effective strategy because it allows people to change the underlying appraisals that contribute to negative emotions (Gross, 1998; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Since reappraisal involves cognitively reframing an event to reduce the negative emotions you feel. It helps people view stress as a positive challenge rather than a negative threat, so that they can manage stress better.

Empirical evidence consistently indicates that cognitive reappraisal is beneficial for psychological health. It is the best studied strategy because its core elements are central to many forms of therapy, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) (Beck 2005), dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT).

The Advantages of The Reappraisal Strategy

The advantages of the reappraisal strategy are (Milyavsky et al., 2019):

- The advantage of cognitive reappraisal is that it allows people to change their emotional responses to the situation without escaping the situation (as happens in the distraction technique) or running away from the emotion itself (as happens in the suppression technique).

- reappraisal leads to better personal and interpersonal outcomes (Gross & John, 2003; Ortner, Ste Marie, & Corno, 2016; Sheppes & Gross, 2011). For instance, reappraisal is more effective than suppression in reducing negative emotions and negative mood (Evers, Marijn Stok, & de Ridder, 2010; Heilman, Cris¸an, Houser, Miclea, & Miu, 2010; Johns, Inzlicht, & Schmader, 2008; Ortner et al., 2016). Gross and John (2003) also found that people who reported habitually using reappraisal in daily life tended to experience and express more positive and less negative emotions than those who predominantly used suppression.

- Moreover, reappraisal has been linked to better well-being and life satisfaction, and individuals who habitually used reappraisal had closer relationships with their peers, were more liked by others, and received more social support (relative to habitual suppressors; Gross & John, 2003; except see Haines et al., 2016).

Response Modulation

Response modulation occurs once you have felt the emotion. Rather than letting the emotion overwhelm and dominate you, you decide to change how you react to or express it. Response modulation is designed to modify an emotion after it has been fully generated. Most importantly, Gross (1998a) believes that emotions can be modulated or changed, and modulation is what determines the final emotional response. This reduces or increases the emotional impact. For example, your colleague made a mistake that affects your project, which makes you angry in the moment, but you decide not to express your anger to avoid amplifying the emotion or creating discord.

Don’t forget that every emotion, even the most painful ones, deserves to be acknowledged with compassion, without dramatising it or feeling guilty. Feeling emotions, whether pleasant or not, is part and parcel of good mental health.

According to Goldin, Jazaieri, and Gross (2014), suppression, or volitional inhibition of verbal and behavioural expressions of emotions, is the most frequent form of response modulation. It involves pushing away thoughts and feelings that are not comfortable, for example, taking alcohol numb them.

Suppressing emotions may cause temporary relief, but it can lead to various mental and physical problems subsequently. Research shows that frequent expressive suppression may be dysfunctional as it can result in diminished control of emotion, interpersonal functioning, memory, well-being, and greater depressive symptomatology (Gross and John, 2003).

If your emotions are overwhelming, persistent or interfere with your daily activities, it is important to seek mental health support.

References

Beck, A. T. (2005). The Current State of Cognitive Therapy: A 40-Year Retrospective. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953

Evers C, Marijn Stok F, de Ridder DT. Feeding your feelings: emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010 Jun;36(6):792-804. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371383. Epub 2010 May 11. PMID: 20460650.

Haines, S.J., Gleeson, J., Kuppens, P., Hollenstein, T., Ciarrochi, J., Labuschagne, I., Grace, C. and Koval, P., 2016. The wisdom to know the difference: Strategy-situation fit in emotion regulation in daily life is associated with well-being. Psychological Science, 27(12), pp.1651-1659.

Heilman RM, Crişan LG, Houser D, Miclea M, Miu AC. Emotion regulation and decision making under risk and uncertainty. Emotion. 2010 Apr;10(2):257-65. doi: 10.1037/a0018489. PMID: 20364902.

Biggs, A., Brough, P. and Drummond, S., 2017. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice, pp.349-364.

Goldin, P.R., Jazaieri, H. and Gross, J.J., 2014. Emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. In Social anxiety (pp. 511-529). Academic Press.

Gross, J.J., 2015. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological inquiry, 26(1), pp.1-26.

Gross, J.J., 1998. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of general psychology, 2(3), pp.271-299.

Gross, J.J., 2008. Emotion regulation. Handbook of emotions, 3(3), pp.497-513.

Gross, J.J., 2013. Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion, 13(3), p.359.

Gross, J.J. and John, O.P., 2003. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), p.348.

Johns M, Inzlicht M, Schmader T. Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: examining the influence of emotion regulation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2008 Nov;137(4):691-705. doi: 10.1037/a0013834. PMID: 18999361; PMCID: PMC2976617.

Milyavsky, M., Webber, D., Fernandez, J.R., Kruglanski, A.W., Goldenberg, A., Suri, G. and Gross, J.J., 2019. To reappraise or not to reappraise? Emotion regulation, choice and cognitive energetics. Emotion, 19(6), p.964.

Ortner, C.N.M., Ste Marie, M. and Corno, D., 2016. Cognitive costs of reappraisal depend on both emotional stimulus intensity and individual differences in habitual reappraisal. PloS one, 11(12), p.e0167253.

Ortner CN, Ste Marie M, Corno D. Cognitive Costs of Reappraisal Depend on Both Emotional Stimulus Intensity and Individual Differences in Habitual Reappraisal. PLoS One. 2016 Dec 9;11(12):e0167253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167253. PMID: 27936022; PMCID: PMC5147884.

Sheppes, G. and Gross, J.J., 2011. Is timing everything? Temporal considerations in emotion regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), pp.319-331.

Sheppes, G. and Gross, J.J., 2012. Emotion regulation effectivenGross, J.J., 2013. Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion, 13(3), p.359.ess: What works when. Handbook of psychology, 2, pp.391-406.

Troy, A.S., Shallcross, A.J., Brunner, A., Friedman, R. and Jones, M.C., 2018. Cognitive reappraisal and acceptance: Effects on emotion, physiology, and perceived cognitive costs. Emotion, 18(1), p.58.

Yarwood, M. (2022). Psychology of Human Emotion: An Open Access Textbook. [online] psu.pb.unizin.org. Affordable Course Transformation: Pennsylvania State University. Available at: https://psu.pb.unizin.org/psych425/.