“The greatest challenge in life is to be our own person and accept that being different is a blessing and not a curse. A person who knows who they are lives a simple life by eliminating from their orbit anything that does not align with his or her overriding purpose and values. A person must be selective with their time and energy because both elements of life are limited.”

― Kilroy J. Oldster, Dead Toad Scrolls.

By Kenneth Ukoh, November 11, 2022

In Part 5, we will discuss conation. We initially wanted to include it in Part 6 on self-regulation, but because of its importance for effective goal pursuit, we have decided to discuss it here on its own.

The main benefit of pursuing goals is to enable people to improve themselves and their well-being, as the process of goal pursuit and attainment is meant to bring about changes and new organisations into people’s lives. However, when we refer to improving themselves, which selves are we referring to? What is the “self” that people use when setting goals? Are people striving to become their ideal selves or ought selves? We will answer this question by examining the idea of self-knowledge, as there are different ways of understanding the self.

According to the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, self-knowledge is “one’s own mental states—that is, of what one is feeling or thinking, or what one believes or desires” (Gertler, 2021). It is also defined as “actual genuine information one possesses about oneself (Carlson, 2013; Vazire & Carlson, 2010). It includes information about one’s personality traits, typical emotional states, needs and goals, values, opinions, beliefs, preferences, physical attributes, relationships, behavioural patterns, and social identity (Morin & Racy, 2021). It is different from self-concept because self-concept “is the image one develops about oneself (Marsh & Shavelson, 1985), which, unlike self-knowledge, may or may not be realistic. Self-concept is characterised by beliefs about the self, based on self-information (Campbell et al., 1996), whereas self-knowledge is supported by various types of evidence external to the self. Indeed, self-knowledge is commonly measured by looking at the degree of agreement” (Morin & Racy, 2021). So, self-knowledge is needed before you can select and pursue attainable and beneficial goals. We will now discuss different aspects of self in the next section under the self-discrepancy theory.

The Self-Discrepancy Theory

Research has shown that what motivates people to pursue goals is the gap or discrepancy in their lives between their desired future states and their current states. A goal is used to reduce or eliminate that discrepancy. Tory Higgins ’ self-discrepancy theory proposes that individuals possess three self-domains: the current self, the ideal self, and the ought self (Higgins, 1987).

- The actual self. This “is your representation of the attributes that someone (yourself or another) believes you actually possess” (Higgins, 1987). Your real or current self represents who you are and how you think, feel, look, and act. The real self can be seen by others, but because you have no way of truly knowing how others view you, the real self is your self-image.

- The ideal self. This is your representation of the attributes that someone (yourself or another) would like you, ideally, to possess (i.e., a representation of someone’s hopes, aspirations, or wishes for you).” (Higgins, 1987). The ideal self is how you want to be. It is your best and idealised image that you have developed over time, based on what you have learned and experienced. The ideal self could include components of what your parents have taught you, what you admire in others, what our society promotes, and what you think is in your best interest.

- The ought self. This “is your representation of the attributes that someone (yourself or another) believes you should or ought to possess (i.e., a representation of someone’s sense of your duty, obligations, or responsibilities).”, (Higgins, 1987). The ought self tends to be concerned with safety and responsibility.

As social beings, others influence who we believe we are or who we would like to be and want to become. Family, culture, media, and the environment all play a role in shaping who we think we are and how we feel about ourselves. These are powerful socialising influences that we must be mindful of when selecting our goals to ensure that they align with our interests. Though people’s influences can be beneficial in shaping our self-image, such influences must be treated objectively.

Self-Standpoint and Self-Guides

Higgins (1997) also relates self-domain to different self-state representations known as “standpoints on self” He identifies two basic standpoints on self and defines a “standpoint “as a point of view from which you can be judged that reflects a set of attitudes or values. This may be:

- An individual’s own personal standpoint

- The standpoint of significant people in the person’s life, such as mother, father, sibling, spouse, close friends, etc. A standpoint may be different between these people.

When each self-domain is combined with each standpoint on self, they produce six basic types of self-state representations as follows:

- Actual/own

- Actual/other

- Ideal/own

- ideal/other

- Ought/own

- Ought/other

According to Higgins (1997), the first two self-state representations are typically known as “self-concept”. The last four self-state representations are self-directive standards or acquired guides for being or “self-guides.” The American Psychological Association (APA) Dictionary of Psychology defines self-guides as “a specific image or standard for the self that can be used to direct self-regulation. In particular, self-guides include mental representations of valued or preferred attributes; that is, ideals and notions of how one ought to be. These may be chosen by the self or may come from others” (APA Dictionary of Psychology – self-guide, n.d.). Self-guide is an essential concept in social psychology. It has motivational implications and is involved in self-regulation, particularly goal-striving.

Self-Concept and Self-Guides

The self-discrepancy theory holds that people are motivated to reach a condition where their self-concept matches their personal self-guide. Not everyone is expected to possess all the self-guides. Some people may possess only ought self-guides, whereas others may possess only ideal self-guides. eople differ according to their self-guides (i.e., ideal or ought self) that are prominent in their lives which they use to evaluate themselves. This discrepancy can affect their emotional well-being as stated below (Werner, 2019):

- When there is a discrepancy between an individual’s actual and ideal selves, they are more likely to experience dejected, such as disappointment, dissatisfaction, and sadness because they are not living up to their full potential (e.g., there is a lack of positive outcomes).

- When there is a discrepancy between an individual’s actual and ought selves, they are likely to experience more high arousal, and negative emotions, such as agitation, threat, or fear that stem from the presence of negative outcomes (Barnett, Moore, & Harp, 2017; Carver, Lawrence, & Scheier, 1999; Higgins, 1987).

- Additional studies have found that both actual-ideal and actual-ought discrepancies are positively related to experiences of hopelessness, depression, and suicide ideation in students (Cornette, Strauman, Abramson, & Busch, 2009), whereas a reduction in the actual-ideal discrepancy resulted in positive therapeutic changes (Berking, Grosse Holtforth, & Jacobi, 2003).

- While some level of discrepancy is to be expected and is likely to be motivating during goal pursuits, experiencing chronic discrepancies can leave a person feeling shameful, guilty, and lacking motivation so that they impede the progress that they make on their goals.

If the real self matches the ideal self), the individual is likely to feel a sense of mental well-being or peace of mind. According to Boyatzis and Akrivou, (2006), “the ideal self (IS) is an evolving, motivational core within the self, focusing a person’s desires and hope, aspirations and dreams, purpose and calling. Discrepancies or congruence between the actual (i.e. real self) and the person’s ideal self result in unique emotional and behavioural consequences (Boldero and Francis, 1999). The ideal self serves a mechanism linked to self-regulation; it helps to organize the will to change and direct it, with positive affect from within the person.”

Self-Discrepancy and Promotion/Prevention Goals (Approach-Oriented Goals)

In Part 4 we talked briefly about promotion and prevention goals while discussing the types of goals. Higgins, (1997), differentiates between promotion-focused individuals (promotion-oriented goals) and prevention-focused individuals (prevention-oriented goals). Self-regulation with a promotion focus is characterized as the motivation to attain growth and nurturance and to bring one’s actual self into alignment with one’s ideal self, as well as the desire to reach gains (and to avoid non-gains). That kind of system is discrepancy-reducing and involves attempts to move the currently perceived actual self-state as close as possible to the desired reference point. By contrast, a self-regulatory system with a negative reference value has an undesired end state as the reference point. This system is discrepancy amplifying and involves attempts to move the currently perceived actual self-state as far away as possible from the undesired reference point (a prevention-oriented goal).

The idea of moving towards pleasure and avoiding pain is normal human behaviour and can be traced back to the concept of hedonism in Greek philosophy. It is similar to the idea of approach and avoidance motivation. Approach motivation indicates a propensity to move toward (or maintain contact with) the desired stimulus. Avoidance indicates a propensity to move away from (or maintain distance from) an undesired stimulus (Feltman and Elliot, 2012).

According to Psychology Today, research has shown that the pursuit of a greater number of avoidance goals is related to (Pychyl, 2009):

- Less satisfaction with progress and more negative feelings about progress with personal goals

- Decreased self-esteem, personal control and vitality

- Less satisfaction with life

- Feeling less competent in relation to goal pursuits

A common example of avoidance is procrastination. This shows that avoidance goals do not enhance progress.

The Importance of Self-Knowledge and Choosing the Right Goal – The Concepts of Conation

We discussed the importance of deciding on what goals to pursue so that you do not choose the wrong goals in part 4. The lack of accurate self-knowledge as discussed above can cause people to choose the wrong goals. According to Sheldon and Elliot, (1999), people may attain their goals without feeling happier or better than before or they may even abandon them pursuing them to the end. It is the failure of the conative process when people choose the wrong goals. It is one of the reasons for ineffective goal pursuit because people fail to evaluate why they want to attain their goals sufficiently. The SMART goals method is also to blame for this failure as goals are evaluated on the basis of complying with that method despite their self-guides. For this reason, many people don’t select goals based on their self-knowledge to reflect their own implicit motivations, inner desires, and potentials. So, they select goals that do not serve them well (Sheldon, 2014).

Psychologists have traditionally divided the study of the mind into three components: cognition, affect and conation. These three dimensions of the mind work together, but the reason that not much is known about conation is that the focus of the studies in psychology has been on cognition and emotion. But neither of those two drives action and directs the way we turn ideas or goals into real results. This is the work of the conative dimension of the mind. However, studies in conation are receiving more attention now because it has been realised that conative skills are the skills needed to thrive in the 21st century.

According to Huitt and Cain, (2005), “cognition refers to the process of coming to know and understand; of encoding, perceiving, storing, processing, and retrieving information. It is generally associated with the question of “what” (e.g., what happened, what is going on now, what is the meaning of that information.)”, affect is defined as “the emotional interpretation of perceptions, information, or knowledge. It is generally associated with one’s attachment (positive or negative) to people, objects, ideas, etc. and is associated with the question “How do I feel about this knowledge or information?”.

What Is conation?

In an overview of the domain of conation by Huitt and Cain, (2005), conation is defined as “the connection of knowledge and affect to behaviour and is associated with the issue of “why.” It is the personal, intentional, planful, deliberate, goal-oriented, or striving component of motivation, the proactive (as opposed to reactive or habitual) aspect of behaviour (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven & Tice, 1998; Emmons, 1986).” The APA Dictionary of Psychology defines it as “The proactive (as opposed to habitual) part of motivation that connects knowledge, affect, drives, desires, and instincts to behaviour. Along with affect and cognition, conation is one of the three traditionally identified components of mind. The behavioural basis of attitudes is sometimes referred to as the conative component” (APA Dictionary of Psychology – Conation, n.d.)

According to Kathy Kolbe (Kolbe, 2009), “The conative part of the brain is the third piece of the tripartite mind, the cluster of human instincts that drives creative problem-solving. Understand conation and you’ll understand the approaches you’re naturally driven to take. Acting according to your natural abilities will, in turn, maximize your success and well-being.” In other words, intelligence measures IQ while emotion measures how you feel. Conation is that part of the brain that organises those thoughts and feelings and directs them to our daily activities in life. Kathy Kolbe is an acclaimed theorist, educator, organizational strategist, and the founder of Kolbe Corp and the Center for Conative Abilities. She is the world’s leading authority on human instincts and conation.

In view of the importance of conation as defined above, Huitt & Cain, (2005) suggest that when selecting goals, people need to consider the following as they are some of the conative issues people face in life:

- What is my life’s purpose and are my actions congruent with that purpose?

- What are my aspirations, intentions, and goals?

- On what ideas, objects, events, etc. should I focus my attention?

- What am I going to do, what actions am I going to take, and what investments am I going to make?

- How well am I accomplishing what I set out to do?

So, an effective goal pursuit starts with understanding the role that conation plays in goal pursuit. If a person lacks the conative capacity, the person is likely to fail in his or her goal pursuit, irrespective of how “SMART” the method used to pursue the goal is. If the resources used to publicise and popularise the SMART goals method had been used to popularise conation, many people would be setting and achieving their goals. That would make the world a better place as many people would be attaining their goals and improving their well-being.

The Process of Conation

Huitt and Cain, (2005), suggest the following three approaches to understanding conation:

- Kolbe’s conative style

- The organisation of the conation

- The process of conation.

The process of conation is what we are going to talk about next as it is associated with intrinsic motivation. When people understand the process of conation it can help them to develop conative competencies which will facilitate the attainment of their goals.

Our discussion here is based on an overview of the domain of conation by Huitt and Cain, (2005) which approaches conation in relation to three aspects of motivation: directing, energizing, and persisting. The conative style approach will be discussed later.

Directing

There is a growing interest now in people wanting to live meaningful lives. Research has shown that meaning in life is what broadly drives people to pursue goals because when people are focused on what gives their lives meaning, they are generally more agentic and inspired (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

Huitt and Cain, (2005) have identified the following five main components of conation in relation to directing: identifying one’s purpose; identifying human needs; aspirations, visions, and dreams of one’s possible futures; making choices and setting goals and developing an action plan.

Identifying One’s Purpose

The need for purpose in life has become prominent these days as a considerable amount of scientific research has been focused on it. This has prompted people to seek meaning in their lives as living a life of purpose is believed to lead to a meaningful life. Purpose has been defined as a “Central, self-organizing life aim. Central in that when present, purpose is a predominant theme of a person’s identity. Self-organizing in that it provides a framework for systematic behaviour patterns in everyday life” (Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009). Purpose directs our lives not only in terms of the purpose for our personal lives but also shapes our worldview philosophy. In other words, purpose provides a central self-organising and predominant life theme in the following ways:

- Directing life goals and daily decisions

- Guiding the use of finite personal resources

- It does not govern behaviour, rather, it offers direction like a compass, but people have the choice to accept or reject their purpose and go in a different direction.

- It is the self-sustaining source of meaning through goal pursuit and goal attainment.

- Our purpose is woven into a person’s identity and behaviour as a central, predominant theme—central to personality as well.

Viktor Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist and neurologist, the founder of logotherapy and a Holocaust survivor. Frankl adopted the existential philosophy that humans are motivated by the desire to find meaning in life. He argued that life can have meaning even in the most difficult of circumstances because the search for meaning is what drives human behaviour Bushkin and van Niekerk, (2021).

His experience and the loss of the lives of his wife, parents, and brother in the concentration camp tested his view that it is through a search for meaning and purpose in life that individuals can endure hardship and suffering. Frankl has shaped modern psychological thinking. He lectured at more than 200 universities and authored 40 books published in 50 languages and received 29 honorary doctorates. His ideas and experiences relating to the search for meaning in life have influenced theorists, practitioners, researchers, and laypeople all over the world.

Research has overwhelmingly shown that people who live with a sense of purpose have the following advantages:

- They have better health (Suttie, J., 2020).

- They live longer (Suttie, J., 2020).

- They are more successful economically (Suttie, J., 2020)

- Broadly, meaning drives concordant goal pursuit. Self-concordant goals are autonomous goals that express enduring interests and values (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999).

- Research identifies meaning as a coping resource and further reveals its motivational nature (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

- They can endure hardship, suffering even life-threatening situations

- The well-being of any society is directly related to the well-being of the individuals in society. Since meaning in life supports individual flourishing, it is also related to societal flourishing. Studies have identified social bonds as a primary source of meaning in life (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

Watch out for our series on purpose soon!

Identifying Human Needs

Human needs are commonly regarded as the driver of human actions. Abraham Maslow in his study popularly known as the Hierarchy of Needs, which provided the landmark for the study of motivation, identified five basic categories of needs: physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization (McLeod, 2018, May 21). However, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory is without criticisms and one of the main criticisms is the inability to test it empirically. Now, there is no unanimous agreement by researchers as to what human needs really are since there are many theories of motivation. For instance, research within self-determination theory has identified three basic psychological needs: “autonomy”, “competence “, and “relatedness” (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2017) which have been shown to enhance self-motivation, mental health and well-being. Other popular studies are the need for achievement (McClelland, 1992) and the need for meaning in life (Frankl, 1997). For example, McClelland says that, regardless of our gender, culture, or age, we all have three motivating drivers, and one of these will be our dominant motivating driver. This dominant motivator is largely dependent on our culture and life experiences. These are the need for “achievement”, “affiliation” and “power.” McClelland’s theory can help people to identify their dominant motivators and then use this information to influence how they set goals.

Interestingly, The Human Givens Institute has developed holistic human needs based on many years of research (The Human Givens Institute, n.d.). These are:

- Security. A safe territory and an environment which allows us to develop fully

- Attention. Everybody needs to give and receive attention. It is seen as a form of nutrition

- Autonomy. Everyone needs a sense of autonomy and control by having the free will to make responsible choices

- Emotional intimacy. The need to be accepted for who we are

- Connectedness. Feeling part of a wider community

- Privacy. Opportunity to reflect and consolidate experience

- Sense of status. The need to have a sense of status within social groupings

- Sense of competence and achievement. Having a sense of competence and achievement gives people the self-satisfaction that they are significant and can exert a meaningful influence on their environment

- Meaning and purpose. Meaning and purpose are fundamental needs of human beings to help people organise and transcend themselves

Identifying Your Possible Self

We have already talked about self-concepts and self-guides representing the different ways we see ourselves. According to Markus and Nurius, (1986), possible selves are defined as “the cognitive components of hopes, fears, goals, and threats, and they give the specific self-relevant form, meaning, organization, and direction to these dynamics.” They represent the ideas of individuals of what they might become (future self), what they would like to become (ideal self) and what they are afraid of becoming (feared self). In other words, “The possible selves that are hoped for might include the successful self, the creative self, the rich self, the thin self, or the loved and admired self, whereas the dreaded possible selves could be the alone self, the depressed self, the incompetent self, the alcoholic self, the unemployed self, or the bag lady self” (Markus and Nurius 1986).

Knowing the possible selves is important because:

- They function as incentives for future behaviour (i.e., they are the selves to be approached or avoided). An example is promotion and avoidance motivation goals which we have already discussed here and elsewhere in these articles.

- They provide an evaluative and interpretive context for the current view. They determine the direction of change and motivate the person to take action in order to realize the hoped-for visions of the self and to prevent the realization of the feared ones.

- They provide the bridge to action. When something is considered possible it encourages individuals to set goals and create plans for achieving them.

- Visions, dreams, aspirations and hopes feed the possible selves. This conative process gives them visual and emotional elements that make them effective and reachable.

Making Choices and Setting Goals for Visions, Aspirations or Dreams

Life-changing and transformational goals are more than routine types of goals. When our goals are based on our values or visions, they are meaningful. A sense of doing something meaningful is a key element of happiness. So, goals allow us to pursue the aspirations of our own choice and enjoy a feeling of achievement when we attain them.

When we pursue goals that matter the most to us, we can become attuned to our inner strengths as well as our passions. Using our strengths when doing something has numerous benefits. Studies show that knowing and leveraging our strengths can increase our confidence, and boost engagement, according to an article on the Forbes website (Suner, 2020).

In addition, meaning in life is regarded as a personal resource that helps people cope with stress, uncertainty, anxiety, and trauma. It also promotes societal flourishing economically. Since meaning generally promotes self-control and goal-directed behaviour, it is likely to influence the types of economic decisions that people make regarding their work and careers. This leads to greater financial security for individuals within the community which is the key to the economic health of their community and the global economy. When individuals are better positioned to support other important aspects of community life such as charities, they are contributing to the well-being of society (Routledge & FioRito, 2021).

Directing the Development of Implementation Plans

The final aspect of directing is the development of plans so that the goal can be actualised. It can be recalled that the conative domain is associated with goal-directed action.

An action plan lays out the tasks to be completed to accomplish your goal. A good action plan lays out all the necessary steps to achieve your goal and helps you reach your target efficiently by allocating resources, and a timeline, including the start and end dates of every step in the process. The level of detail in the action plan can vary depending on the resources you have and the complexity of the goal.

Huitt & Cain, (2005), suggest the use of two activities: backwards planning and task analysis. Backward planning is also known as backward goal-setting or backward design, and it is often used in education and training. It is also said to be used extensively in the US Army. This involves starting with the desired end results and then identifying the most immediate state and the required procedures to meet that result. Starting at the end and looking backwards enables you to mentally prepare yourself for success as you can map out the specific milestones you need to reach. In addition, it enables you to identify where you need to pay particular attention in your plan to facilitate the achievement of your goal.

To be successful, backward planning must be followed by a task analysis that will identify the prerequisite skills and knowledge that are required to learn or perform the specific task. A task analysis increases productivity by streamlining the work processes and clarifying every aspect of a task.

Gollwitzer, (1999) suggests the use of implementation intentions. Implementation intentions usually take the form of for example, “If situation Y occurs, then I will do X behaviour.” The situation then becomes an automatic trigger for the behaviour when it comes up in real life.

Research has shown that implementation intentions are effective for promoting the initiation of goal striving, the shielding of ongoing goal pursuit from unwanted influences, disengagement from failing courses of action, and conservation of capability for future goal striving. In addition, the formation of implementation enhances “the accessibility of specified opportunities and automated respective goal‐directed responses” (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006).

Energizing

The goal-pursuit process involves moving in new directions and changing behaviour. For this reason, there is always some discomfort involved because it takes people out of their comfort zones to develop new thoughts and behaviours. So, we need to have a strategy for energising us.

Energising is defined by Psychology Dictionary as the “mental skill we use when we are tired.” One energising strategy is to choose a self-concordant goal which will be discussed later in Part 6 of these articles. Such a goal aligns with the person’s self-interest or is commensurate with the person’s self-guides.

According to Psychology IResearch, energising strategies are sometimes known as activation strategies and they are primarily designed to boost the mental or physical level of task performance. They are techniques for increasing arousal and are commonly used in sports when athletes are not psyched-up enough for their activity and competition. They may also be used to overcome fatigue during competition. They include techniques such as combining controlled breathing with positive self-talk, affirmations, positive verbal cues, imagery and visualisation (Strength Model Of Self-Control, n.d.).

In an article in Psychology Today, a study was conducted to show whether mental energy is just a metaphor i.e. when we refer to being energized to pursue a goal, is this energisation in the mind or does that energy translate to physiological energy that affects the rest of the body? “This study suggests that getting mentally energized to achieve a goal creates physiological energy. That energy is reflected both in a change in blood pressure as well as an increased ability to perform a physical task” (Markman, 2014).

Persisting

Persistence is a multidimensional concept, though efforts are being made to unify all the different concepts. For example, (Moshontz & Hoyle, 2020) propose a general model of persistence. They argue that persistent goal pursuit results from three processes:

- Resisting the urge to give up

- Recognizing opportunities for goal pursuit

- Returning to pursuit

Persistence is defined on the Authentic Happiness website (Dean, n.d.), as the “voluntary continuation of a goal-directed action in spite of obstacles, difficulties, or discouragement” (Peterson and Seligman, 2004, p. 229). The authentic Happiness website is part of the Positive Psychology Center directed by Dr Martin E. P. Seligman, Professor of Psychology at Penn. The American Psychological Association (APA) Dictionary of Psychology defines it as (Dean, n.d.):

- “Continuance or repetition of a particular behaviour, process, or activity despite cessation of the initiating stimulus”

- “The quality or state of maintaining a course of action or keeping at a task and finishing it despite the obstacles (such as opposition or discouragement) or the effort involved. Also called perseverance”

- “Continuance of existence, especially for longer than is usual or expected”

According to Huitt and Cain, (2005), persistence is increasingly recognized as an important component of conation that generally facilitates success. For example, Goodyear (1997), in a review of the literature regarding the success of professional psychologists, found that while there are “threshold levels” of intellectual and interpersonal skills, motivation and persistence were even more important in predicting levels of expertise.

Persistence and Conscientiousness

Howard and Crayne, (2019) define it as ” the personal tendency to endure through hardships to achieve goals, is highly valued within organizations. In the“era of the startup” (Zwilling, 2013), people are praised for undertaking heavy entrepreneurial challenges, and their persistence is regularly considered a key predictor of success (Dimotakis, Conlon, & Ilies, 2012; Gilbert, 2009; Trougakos, Jackson, & Beal, 2011). According to them, these are some of the concepts that are associated with persistence and sometimes some of them are used interchangeably: “goal striving, goal commitment, industriousness, grit, tenacity, stamina, conscientiousness, perseverance.”

Skills associated with persistence are engaging in daily self-renewal activities; monitoring one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviours; self-evaluation based on the monitoring data collected; reflection on progress made; and the completion of tasks. So, persistence may be a state or condition in which people are stimulated toward a goal or a personal trait possessed by some people since conscientiousness, one of the big five personality traits also means the same thing.

Persistence, self-efficacy, and self-esteem are related. In general people with higher self-esteem are more likely to persist on a difficult task than people with lower self-esteem because if you believe you are competent, you have a good chance of succeeding at most things, and you are less likely to quit.

There is a phenomenon called self-handicapping. This happens when people fail to persist. It involves engaging in a behaviour that is known to hamper performance, such as drinking, not studying in preparation for examinations, or not working hard. It may also happen when a goal that is so easy is chosen that success is meaningless or the goal is so difficult that success is not likely.

How to Develop Persistence

Authentic Happiness, Penn suggests the following exercises for building persistence, adapted from a list provided by psychologist Jonathan Haidt at the University of Virginia (Dean, n.d.) :

- Finishing a project ahead of time

- Noticing your thoughts about stopping a task and making a conscious effort to dismiss them. and focusing on the task at hand

- Using a time management aid of some sort (a palm pilot, a daily planner, etc.). Finding a system that works and using it

- Setting a goal and creating a plan for sticking to it

- When waking up in the morning, make a list of things that you want to get done that day that could be put off until the next day. Make sure to get them done that day

According to Huit and Cain, (2005), there are various skills of persistence which can be developed such as:

- Engaging in daily activities that enhance self-renewal

- Monitoring your thoughts, emotions, and behaviours

- Self-evaluation based on the monitoring data collected

- Reflection on progress made

- The completion of tasks to avoid procrastination

In her book, The Science of Success “What Researchers Know That You Should Know,” Professor Paula Caproni distils many years of research that explains what success is and why some people are successful in achieving their goals, while some are not. Below is a summary of the main reasons (Caproni, 2017):

- Having a growth mindset. People who have a growth mindset believe more in nurture than in nature. They believe that intelligence, talents, and good characteristics are learned and can change over time with effort and practice

- Positive core self-evaluations. We usually don’t think much about how our unconscious beliefs affect our abilities to achieve our goals. Research has shown that people who have high core self-evaluations think positively about themselves. They have confidence in their abilities and see the world around them optimistically

- Conscientiousness. They figure out what they are supposed to do, and how they’re supposed to do it and they get it done. They are self-motivated, hard-working, and self-disciplined. They persist until they finish and are willing to delay gratification in order to meet their goals

- Gritty people. Grit is passion and perseverance toward a long-term goal. Gritty people are hardworking and self-regulated. Grit is a function of conscientiousness but it differs from conscientiousness in that grit refers to persevering for a very time

- Social capital. This is the mutual goodwill, trust, cooperation, and influence that you develop through your relationships that help you to get the resources you need to add value to yourself and achieve goals

- Becoming an expert. Deliberate and consistent practice makes an expert. It’s not just practising longer and harder than others, it’s about practising in a more focused, strategic, and structured way day after day and year after year

- Energizers. Energizers are realistic optimists who communicate a compelling vision, They fully engage in their interactions with others, making others feel heard, appreciated, and respected. They show respect for others and faith in people’s abilities to achieve their goals

How to Develop and Improve Conative Skills

Conative skills employ feelings and emotions and harness them in order to enhance productivity. According to Learning Sciences International, they include the following abilities (Sterling, 2014) :

- Interpreting situations

- Cultivating a growth mindset

- Developing resilience

- Avoiding negative thinking

- Taking various perspectives on an issue

- Interacting responsibly with other people

- Ability to handle controversy and resolve conflict

These are skills that can be developed.

According to Huitt & Cain, (2005) conation is related to goal orientation, intrinsic motivation, volition, will, self-regulation, and self-direction. So, there is a considerable amount of research on how to develop conative skills as there is considerable research in these areas. But let us briefly talk about self-regulation here. We will discuss it more in Part 7. Self-regulation is a broad term but in relation to goals, it is defined as a “Dynamic process of determining desired end-point and then taking action to move toward it” (Inzlicht, et al, 2021). So, Self-regulation includes the various ways in which people modify their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours while pursuing personal goals, including engaging in effortful self-control while monitoring progress along the way. Self-control is sometimes used to mean the same thing as self-regulation, but they differ. Self-control is defined as the “Process of advancing one goal over a second goal when the two come into conflict” (Inzlicht, et al, 2021). But the most popular method of setting goals today, the SMART method says nothing about self-regulation.

In connection with learning, Ramdass and Zimmerman, (2011) state that self-regulation involves setting goals, selecting and using strategies, monitoring performance, and repeatedly reflecting on learning outcomes over a lengthy period of time. They also state that self-regulation operates through three areas of psychological functioning that are essential in learning:

- Cognitive (e.g., learning strategies)

- Motivational (e.g., self-efficacy, task value)

- Metacognitive (e.g., self-monitoring and self-reflection)

We will talk more about self-regulation in Part 7 of these articles. For now, we will continue with our discussion on conation.

Self-Regulated Learning and Conation

The discussions above on directing, energising, persisting and self-regulation are also about the skills that are needed to develop and improve conative skills. According to Huitt & Cain (2005), research has identified two perspectives of the focus of research on self-regulated learning as it related to conation. These are the process perspective and the character perspective. The process perspective is concerned with goal-pursuit activities such as setting goals, establishing strategies, using resources, and monitoring progress. The character perspective is the human need for autonomy, which is defined as “independence based upon an individual’s personal will to learn something of perceived value that results in the learner’s discretion of how to best accomplish the desired level of learning” (Huitt & Cain 2005).

Barry Zimmerman is one of the leading self-regulated learning experts. He defines self-regulated learning this way. “Self-regulation is not a mental ability or an academic performance skill; rather it is the self-directive process by which learners transform their mental abilities into academic skills. Learning is viewed as an activity that students do for themselves in a proactive way rather than as a covert event that happens to them in reaction to teaching” (Zimmerman, (2002).

Research shows there is a relationship between self-regulation and “perceived efficacy and intrinsic interest” (Zimmerman, 2002). In other words, learners have to believe they can learn the task, and they need to be motivated by learning and practising. According to research, the actual process of self-regulation can be a source of motivation, even for those tasks that may not be motivating.

Zimmerman (2002) observes that, based on research, self-regulation of learning is not about possessing or lacking a single personality trait. Rather, it is about having the skills to select and adapt to each learning task accordingly. These skills include the following:

- Being able to set specific proximal goals, set standards and plan.

- Adopting powerful strategies that help to attain the goals

- Keeping records and monitoring performance and progress

- Adapting one’s physical and social context to goals such as selecting or arranging the physical setting, isolating and eliminating or minimising distractions, and breaking up study periods and spreading them over time.

- Being able to manage efficiently.

- Being able to self-evaluate one’s methods.

- Attributing causation to Results

- Adapting future methods.

According to Zimmerman (2002), a student’s level of learning has been found to vary based on the presence or absence of these key self-regulatory processes (Schunk & Zimmerman, 1994; 1998).

Kolbe’s Conative Style

Kolbe (1990) suggests that human beings have a conative style or a preferred method of putting thoughts into action or interacting with the environment. In other words, each person has a Method of Operation termed “MO”. Kolbe has also developed the Conative A Index, also known as Conative Strengths. This is different from personality type tests. It is a measure of a person’s strengths and natural abilities in how the person prefers to act or solve problems when he or she is at his or her best. In other words, it is the measure of a person’s “MO” or “Method of Operation”. The Kolbe A Index rates the strength of your preference on a scale of 1-10 (10 is high) for each of the four Action Modes.

Kolbe identifies four action or conative modes:

- Fact Finder. The instinctive need to probe and the way we gather and share information. Behaviour ranges from gathering detailed information and documenting strategies to simplifying and clarifying options. This Action Mode handles details and complexity and provides past perspectives.

- Follow Thru. Their instinct is to arrange and design. Their behaviour ranges from being systematic and structured to adaptable and flexible. This Action Mode handles structure and order, and promotes focus and continuity.

- Quick Start. The instinctive need to improvise and the way we deal with risk and uncertainty. Behaviour ranges from driving change and innovation to stabilising and preventing chaos. This Action Mode deals with originality and risk-taking and provides intuition and a sense of vision

- Implementor. The instinctive need to demonstrate the way we handle space and tangibles. Behaviour ranges from making things more concrete by building solutions to being more abstract by imagining a solution. This Action Mode manages physical space and provides durability and a sense of the tangible

In Kolbe’s formulation, it is the combination of the striving instinct, reason, and targeted goals that results in different levels of commitment and action.

Kolbe’s research indicates that all individuals are capable of operating, and do operate, in each of the four action modes. A “form” of each of the four action modes was observed in scholars and preschoolers, geniuses and people who were mentally retarded. The “form” is the way a person operates in any given mode, as determined by what the person naturally does or avoids doing. Kolbe identified three Zones of Operation in each action mode. They are “initiate,” “accommodate,” and “prevent.”

- The word “initiate” describes what a person will do, given his or her volitional instinct.

- The term “accommodate” describes what the person is willing to do to respond to people’s needs and situations.

- And finally, “prevent” refers to the unwillingness of a person to get bogged down or “paralyzed” by the actions of others or what that person probably won’t do by natural inclination.

The conative Capacity

From our understanding of conation so far, a high level of conation is an important factor in being productive and competent in solving problems, as intellectual ability alone is not enough. This brings us to the idea of conative capacity.

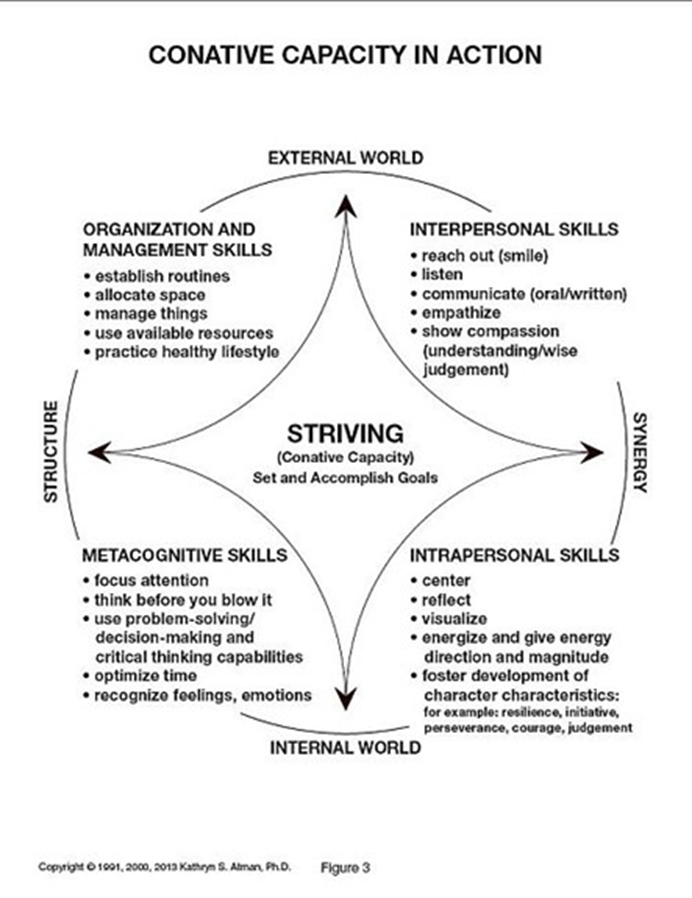

The conative capacity is defined by Atman (2014) as “An organizer that identifies four major life skills, each of which is directly involved in goal setting and goal accomplishment “. It describes the strength of an individual’s striving process. A striving person works vigorously and utilises their energy to achieve what they want. While a person with a weak striving process rarely sets goals and follows through on his or her plans, individuals with a strong conative capacity usually make clear plans to attain their goals and persist till the end.

Source: https://www.kayatman.com/conative-capacity

According to Atman (2014), the conative capacity is divided into segments:

- Vertically, there is the External World at the top and the Internal World at the bottom. The external world is made up of things and personal relationships. The internal world consists of concepts, ideas, and self-understanding.

- Horizontally, there is structure and Synergy. So, when the External World and the Internal World are linked together, vertically, this creates the External and Internal World Structure consisting of two sets of skills: Organisational/Management Skills and Metacognitive Skills. On the other hand, the External and the Internal World of Synergy consist of two sets of skills: Interpersonal Skills in the External World and Intrapersonal Skills in the Internal World.

- When they are linked together horizontally, the External World uses Management/Organisation Skills for Structure. These skills help individuals to organise and manage both things and concepts/ideas. On the Synergy side of the model are listed skills that can help a person deal more effectively with interpersonal relationships and managing oneself. On the structure side of the model are listed specific skills that can help a person organise and manage both things and concepts/ideas.

The four life skill areas identified are listed below. They are skills that can be enhanced based on individual strengths and dispositions.

- Organisation and Management Skills (Planning and Follow-through)

- Interpersonal Skills (Social Sensitivity)

- Metacognitive Skills (Intellectual Capability).

- Intrapersonal Skills (Emotional Stability).

The conative capacity provides a snapshot of the main skills needed for self-regulation and effective goal pursuit. These are competencies and resources that are required for effective goal pursuit, rather than SMART goals.

References

American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology. n.d. APA Dictionary of Psychology – self-guide. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary.apa.org/self-guide> [Accessed 22 August 2022].

Atman, K.S. ed., (2014). Conative Capacity. [online] Kathryn Atman, Ph. D. Available at: https://www.kayatman.com/conative-capacity [Accessed 24 Sep. 2022].

Richard E. Boyatzis and Kleio Akrivou, (2006), “The ideal self as the driver of intentional change”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 25 Iss 7 pp. 624 – 642 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02621710610678454

Brockner, J. and Higgins, E., 2001. Regulatory Focus Theory: Implications for the Study of Emotions at Work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), pp.35-66.

Bushkin, H., van Niekerk, R. & Stroud, L., 2021. Searching for meaning in chaos: Viktor Frankl’s story. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 17(3), pp.233–242.

Caproni, P., 2017. The Science of Success What Researchers Know That You Should Know. [Place of publication not identified]: Van Rye Publishing, LLC, pp.23-151.

Dean, B., n.d. Persistence | Authentic Happiness. [online] Authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu. Available at: <https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu/newsletters/authentichappinesscoaching/persistence> [Accessed 30 August 2022].

Dictionary.apa.org. n.d. APA Dictionary of Psychology – Conation. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary.apa.org/conation> [Accessed 16 August 2022].

Edpsycinteractive.org. n.d. Conation: An important factor of mind. [online] Available at: <http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/conation/conation.html> [Accessed 17 August 2022].

Feltman, R., Elliot, A.J. (2012). Approach and Avoidance Motivation. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_1749

Gertler, Brie, “Self-Knowledge”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/self-knowledge/>.

Gollwitzer, P.M., 1999. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), pp.493–503.

Gollwitzer, Peter & Sheeran, Paschal. (2006). Implementation Intentions and Goal Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of Effects and Processes. First publ. in: Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 38 (2006), pp. 69-119. 38. 10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1.

Goodyear, Rodney K. “Psychological Expertise and the Role of Individual Differences: An Exploration of Issues.” Educational Psychology Review, vol. 9, no. 3, 1997, pp. 251–65. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359458. Accessed 4 Oct. 2022.

Grant, H. and Higgins, E., 2013. Do You Play to Win—or to Not Lose?. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: <https://hbr.org/2013/03/do-you-play-to-win-or-to-not-lose> [Accessed 9 May 2022].

Higgins, E., 1998. Promotion and Prevention: Regulatory Focus as a Motivational Principle. [online] Www0.gsb.columbia.edu. Available at: <https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/mygsb/faculty/research/pubfiles/529/HIGGINSADVANCES_1998REG_FOC_.pdf> [Accessed 22 August 2022].

Higgins, E., 1987. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), pp.319-340.

Howard, M. and Crayne, M., 2019. Persistence: Defining the multidimensional construct and creating a measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, pp.77-89.

Huitt and Cain, S. (2005). An overview of the conative domain. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Retrieved [15 August 2022] from http:/www.edpsycinteractive.org /brilstar/chapters/conative.pdf.

Inzlicht, M., Werner, K. M., Briskin, J. L., & Roberts, B. W. (2021). Integrating models of self-regulation. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-061020-105721

Kashdan, Todd & Mcknight, Patrick. (2009). Origins of Purpose in Life: Refining our Understanding of a Life Well Lived. Psychological Topics. 18.

Kolbe, K., 2009. Conation. [online] E.kolbe.com. Available at: <https://e.kolbe.com/knol/index.html> [Accessed 17 August 2022].

Markman, A., 2014. Mental Energy and Physiological Energy. [online] Psychology Today. Available at: <https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/ulterior-motives/201402/mental-energy-and-physiological-energy> [Accessed 29 August 2022].

McLeod, S. A. (2018, May 21). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Retrieved

from https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Markus, H. and Nurius, P., 1986. Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), pp.954-969.

Mascolo, M. (2014). Worldview. In: Teo, T. (eds) Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5583-7_480

Morin, A. and Racy, F. (2021) (PDF) Dynamic self-processes – Researchgate, Researchgate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348635085_Dynamic_self-processes (Accessed: November 18, 2022).

Powers, J. P., et al. (2020). Self-Control and Affect Regulation Styles Predict Anxiety Longitudinally in University Students. Collabra: Psychology, 6(1): 11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.280

Pychyl, T., 2009. Approaching Success, Avoiding the Undesired: Does Goal Type Matter?. [online] Psychology Today. Available at: <https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/dont-delay/200902/approaching-success-avoiding-the-undesired-does-goal-type-matter> [Accessed 22 August 2022].

Psychology IResearchNet. n.d. Strength Model Of Self-Control. [online] Available at: <http://psychology.iresearchnet.com/papers/strength-model-of-self-control/> [Accessed 8 September 2022].

Ramdass, D. and Zimmerman, B., 2011. Developing Self-Regulation Skills: The Important Role of Homework. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22(2), pp.194-218.

Routledge, C. & FioRito, T.A., 2021. Why meaning in life matters for societal flourishing. Frontiers in Psychology. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601899/full [Accessed September 20, 2022].

Sheldon, K., 2014. Becoming Oneself: The Central Role of Self-Concordant Goal Selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), pp.349-365.

Sheldon, K. and Elliot, A., 1999. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), pp.482-497.

Sheldon, K., Elliot, A., Ryan, R., Chirkov, V., Kim, Y., Wu, C., Demir, M. and Sun, Z., 2004. Self-Concordance and Subjective Well-Being in Four Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(2), pp.209-223.

Sheldon, K., 2019. Which Way Should I Go? | Society for Personality and Social Psychology. [online] Spsp.org. Available at: <https://spsp.org/news-center/character-context-blog/which-way-should-i-go> [Accessed 14 August 2022].

Sterling, S., (2014). Exploring Conative Skills. [online] Learning Sciences International. Available at: https://www.learningsciences.com/blog/exploring-conative-skills/ [Accessed 24 Sep. 2022].

Suner, E., 2020. Council Post: Why Leaders Should Focus On Strengths, Not Weaknesses. [online] Forbes. Available at: <https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2020/02/06/why-leaders-should-focus-on-strengths-not-weaknesses/?sh=590544b73d1a> [Accessed 4 October 2022].

Suttie, J., 2020. Seven ways to find your purpose in life. Greater Good. Available at: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/seven_ways_to_find_your_purpose_in_life [Accessed September 20, 2022].